Parvaneh Etemadi

by Ali Ettehad

(Contemporary Practices vol.13)

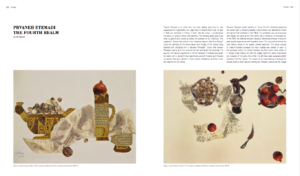

Prvaneh Etemadi is an artist who has been always searching for new expressions for representing her ideas. She was born in Birjand (North East of Iran) in 1948. She began to go to school in Tehran; she explains her days at school: “I didn’t like the school; I countervailed the agony of going to school with painting. This amazing game used to be done by pencils and ended up being the comrade of my childhood.” (1) In Shahdokht high school in Tehran, where she was a student; her literature teacher Jalal Al‐e Ahmad (2) found her painting on the book margin instead of paying attention to what he was teaching. Ale Ahmad found her highly talented and introduced her to Bahman Mohasses (3). During the summer (when the schools are closed) Mohasses used to go to her home as her tutor and teach her drawings. This was the first serious experience in Art for Parvaneh. Except for technique, Mohasses taught her about art in ancient times –his special interest- and specifically ancient Greece and Etruscan civilization. She took interest in those ancient civilizations and that is how she created her first series. Parvaneh Etemadi studied painting in Tehran Fine Art University. She began her career with a tendency towards constructivism and abstraction. She had her first exhibition in late 60s. This exhibition was not convergent with Iranian art scene at the time; but had a reflection of European art. In seventies her attitude changed distinctively and she mixed her past decade experiences with figurative forms. This conjuncture formed the most famous series in her oeuvre; cement paintings. This series consists of cement-mounted canvases; the main impress was formed on each of the canvases before the cement became dry; after that the colors were added to it. Simple linear figures and still life images made the series inconsistent and relevant at the same time; while the still lives were purposely better rendered than the figures. The reason of its inconsistency is because the objects found a more genuine identity and relevant because all the images had the same cement texture. This series was made during the high tide of cement as a material for the interior view of minimalistic buildings in 70s. The cement walls of famous art museums that were built in the 70s could be the best example of such architecture. In this context Etemadi made her works similar to those walls and thus opened a new way for interpreting her works. The next vicissitude in Parvaneh’s oeuvre happened almost a decade later. In 80s her works were mostly painted by colored pencils. She often painted forgotten objects that used to be useful in any Iranian’s home not so long ago. She talks about her grandmother’s old and dusty basement; where was full of old abandoned chests and boxes. This is how the old fabrics, dried pomegranates, hand woven textiles and old objects, etc. enter her body of works. The last series of her works would be her collages. Although she had used this technic before, but her new collages were the result of her searching and experiencing the digital images. Etemadi doesn’t make collages in the cyber atmosphere, but prints digital pictures and makes them a collage by glue and scissor. “We are making collages every day; whether it is mounted on the paper or not. Making the image is what is important; and the resulted image is a collage of all the images we have in mind; that is why the noetic painting ends up with formalism. It is because you can make a collage in the computer of your brain by a few words and a few images. When you are told to get inspiration from nature that is because those images make the mind limitless; while the aesthetic construction of your brain is so uniform. There is only one form of apple and one form of gillyflower in your mind and when you want to paint it just by imagination the result would be the same all the time; and that is why the abstract or noetic painting will always end in repetition”. (4) Parvaneh Etemadi’s collages are a synthesis of her whole oeuvre. She mixes up the simplicity in her cement works, the abstraction of her first series and the past recycling of her colored pencil works to make something magical; the works that are from this world but at the same time seem unbelievably strange and unfamiliar. In Old Persian wisdom, this world is the Sensibilis mundus )The world of things perceived by the human senses( and thus everything in it is empty of verity. Versus this universe is another universe called Mundus intelligibilis (Realm of Ideas) which is sheer truth. As if the Mundus intelligibilis is one standing in front of the mirror, while the Sensibilis mundus is the image through the mirror; something like Plato’s cave. These two universes have no border in common; what connects them is a third universe: the mundus imaginalis. In Persian wisdom the universe of mundus imaginalis is a place where unimaginable notions get translated into visual elements of Sensibilis mundus. Just like Hermes translating the incomprehensible language of Gods and Goddesses of Olympus into the understandable language of mortals. Here this is the mundus imaginalis that has this obligation of interpreting the abstract notions into earthly meanings. The familiar elements of each collage in combination with other elements make an unfamiliar phenomenon that makes the audience ponder; something like the world of Persian Old paintings (Negar gari) that the familiar components of this world make a totally different and unearthly image just by different perspectives and colors functioning like the mundus imaginalis. A dress made of the surfaces of clocks with English and Roman numbers and the elements of Iranian book lay outs, the transparent paper shrouds and dresses, a wrinkled fabric that seems like Iran’s map, Old papers of Islamic art that shaped into containers and dishes from the ancient times and etc. seem to be forming the mundus imaginalis in the contemporary world of Iranians. But all these are neither created for Iranization, nor reviving the subjectivity of Persian wisdom. The artist intuitively created something that the spirit of the past and present of her homeland is fluid in it. ”I painted for fifty years before realizing how Iranian my works was. It was unintentional. On the contrary, I resisted against letting my work take an indigenous taste. I didn’t leave my compositions.”(5) Notes: 1) Selected Works of Parvaneh Etemadi, by Javad Mohabi and Jocelyn Damija, 1960‐98, Honare Iran, 1998, Tehran, Iran 2) Jalal Al‐e Ahmad (Dec. 2, 1923‐ Sep. 9 1969) was an Iranian writer, thinker, and social and political critic. 3) Bahman Mohasses (Feb. 1932‐ 28 Jul. 2010) was a prominent Iranian Artist. 4) An interview with Parvaneh Etemadi, Etemad Melli newspaper, 1 Jan. 2009 5) Paper power, by Muhammad Yusuf, The Gulf Today, June 6, 2013