AN ONLINE COURSE FROM THE HEIRS OF SAFFRON AND SALT PROJECT

LECTURER: ALI ETTEHAD

Background

So young I was, as it is too early when I got seriously attached to literature. Only twelve years old. I got attached to it as it is my profession and me being the professional started to read the top works in the literature world. Imagine how hard this would be at that age. But I attempted to understand them. My days and nights were all about reading the top novels and plays of the world. Started from the classics of the ancient world and slowly coming forward within history. I was eighteen when I reached the 19th century. All these years and even before that, Persian literature was being read in my parental house. Sufis used to gather and read aloud to each other the most important works of ancient Persian literature. Irresistible not to be heard. Even though I thought my mind was busy understanding western texts, my unconscious mind was building an eastern cultural mansion. When I became a film student a little before the age of eighteen, I was lost between the East and the West. Gradually I realized that these two are not apart from each other. I realized that it’s not like they are two different worlds I am trying to understand. It was in those years that I came to the fact of these two being two wings of a palace and losing one will lead to having a fragmentary structure.

My journey to the east started in my nineteens with studying the language of middle Persian of the Sassanid era and after that the Iranian mythology and by the age of twenty-three, I started my search on Iranian mysticism.

And now

Today I am forty and I work as a visual and performing arts artist, a writer and a speaker and it has been ten years since I’ve been teaching what I learned till today to others.

With a comparative study of art history, political history, language history, mythology and mysticism, we can reach a key which by holding on to it, one can open up any door in the field of culture and civilization of nations. I believe that the keyholes which we may confront are much less than the keys we need and if we learn the ancient principles of the world view then the way of attitude, civilizational characteristics and human reactions will be understandable and predictable.

In these years, I have held two main courses: “The Comparative Studies of Iran’s Mysticism, Art and Culture” and “The Comparative Studies of Iranian Mythology, Drama and Rituals”. Both of them are taught in Persian.The first one consists of five semesters of ten sessions and the other is two semesters of ten sessions. Years ago, I wanted to write a course in English, and now the result is a new course titled “Who is Iran?”. This course is a summary of all the contents taught in the Persian courses.

The first semester of this course deals with the civilization and culture of Iran before the beginning of the Islamic era and answers the following questions:

– What are you reminded of when we talk about Iran? History? Culture? Ancient civilization? War? The political state of the recent decades?

– Where does Iran’s name come from? What is the origin of Iran’s name?

– Was there nothing in this geographical area before this name?

– It is known that Iran has 2500 years of history; what was before that?

– In what language did the people of Iran communicate? Was it one language or several languages?

– Which religion did Iranian people believe in? Was it one religion or several religions?

– How far can we go in history?

– Does this search in the past help us in any way?

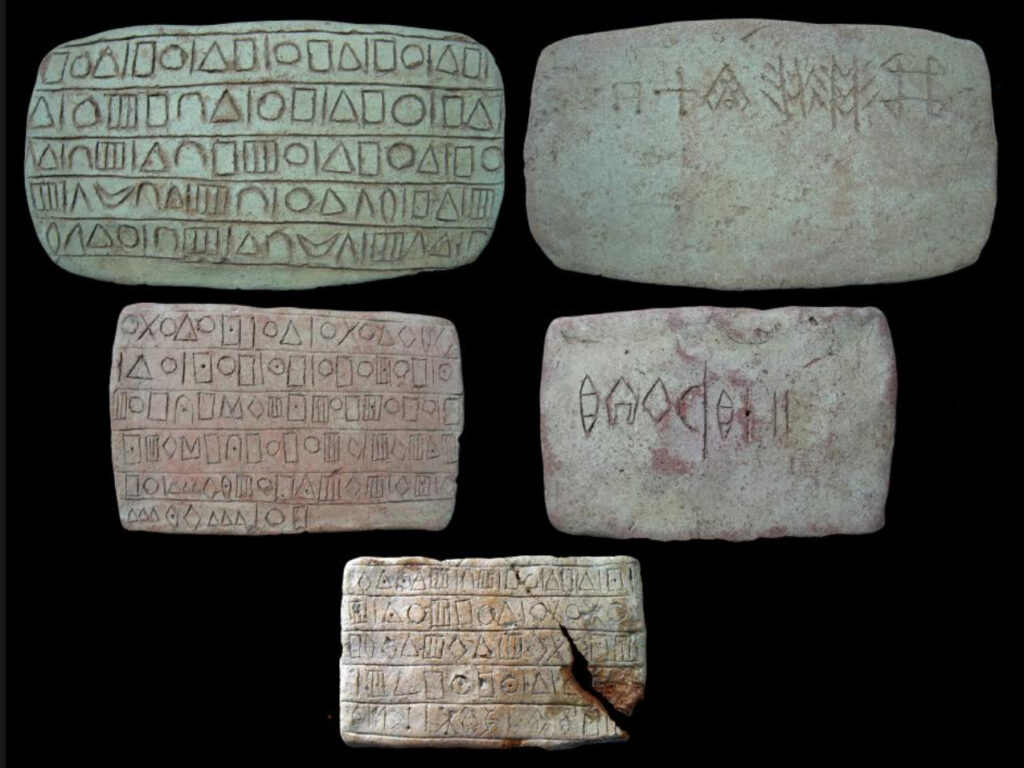

– What are the oldest Iranian texts?

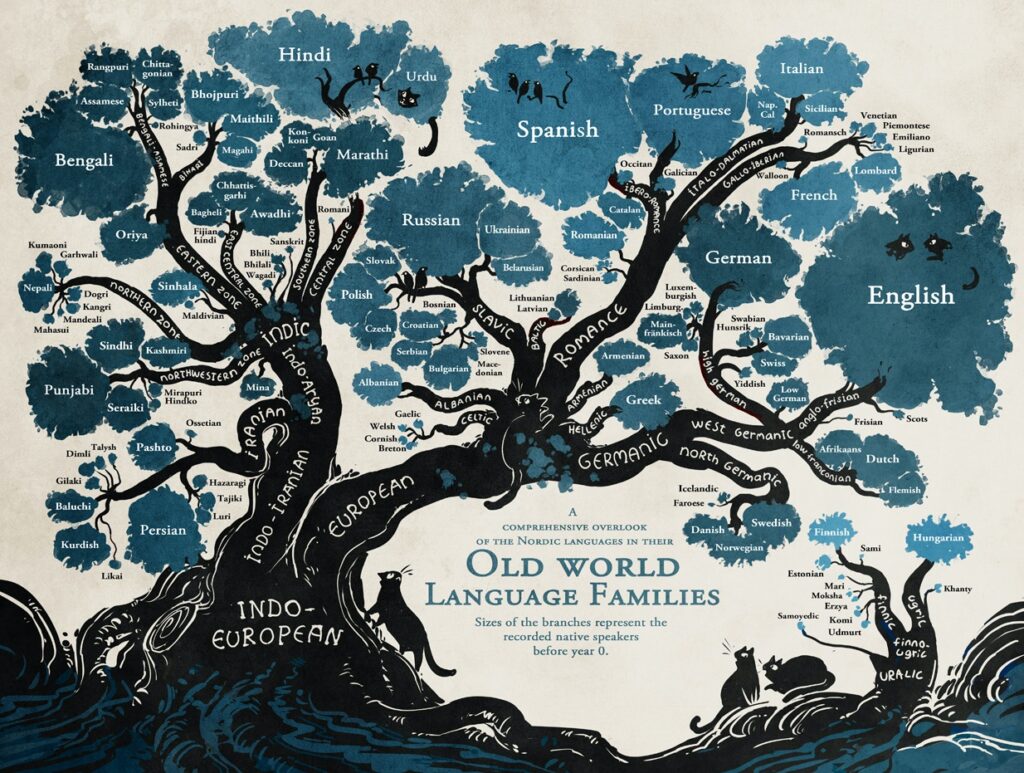

– Do Iranians and Europeans have a shared heritage? How about Iranians and Indians?

– What role does climate play in Iranian culture?

-Which patterns shape the Iranian culture?

-Who is Zaroaster? and what does Zoroastrianism tell us?

-Are the old Iran’s Gods still respected and praised?

– What is the role of time and calendar in Iranian culture?

– How do Iranians perceive time?

– In which ancient texts can we find Iranian pre-Islamic stories?

– In which Iranian texts can we find the roots of many world-famous stories?

– What do myths tell us?

These questions and many others will be answered in one course consisting of ten sessions.

Let’s think about this question: Who is Iran?

Summary of the first semester:

A view about Iran’s pre-Islam culture and civilization Lecturer: Ali Ettehad

(The course consists of eight one-hour sessions)

Why do we need to study history? This is the kind of question that we may have encountered with, many times during our lifetime and each time, different answers were on the way. Ironically enough, the majority of our answers are based on the quotes from known figures of history. I would rather have my own answer to the question. If an alien asks you “what is the most valuable heritage of your kind?” What would your answer be? lots of answers are likely to be on your mind right now and probably lots of them would propose another question with it. If an Alien asks us “How do the people of a community or a civilization feel alliance with one another?” “How come so many of you have fought with each other during your history?” Or if asks “How come a majority come to believe in a common idea-like Christianity-?” What would we say? I believe that these questions and lots of similar ones would eventually lead us to the first question I raised. I believe that the most precious heritage of humanity is storytelling. It is storytelling that made us human rather than being two-legged mammals. Storytelling has brought us together under one flag. Whether it is the flag of homeland, religion, ideology or any other human division. Stories made us strong and weak, invincible and fragile, negotiable and non-negotiable. Now I am going to ask it again; Why do we need to study history? The way I see it, the history of every land is its story, which without knowing it, we can neither understand its people nor the land itself.

All that said, we need to remember that the story of lands is not just the tales of their kings and warriors. The story of a land consists of thousands of pieces, each being only a small piece of a big puzzle and them coming together will make the whole story. Geographical and climatic features, natural phenomena, linguistic features, sacred texts created in the land’s language, words of the wise men and women of the land, the poems and stories of the people, visual and auditory aesthetic interests, religion, spiritual beliefs, visible and invisible creatures of the land. Each of these is the one who treats the story of a land and in a more similar word, these are the elements which make the history of it. Remember that, before getting aware of these stories, us, the humans, were nothing but some scattered herds. Just as if we look at the prehistoric human distribution map, we’ll see that the lands are nameless, and there is no talk or discussion about civilization or culture and the only subject in question is homo species. In the “Who is Iran?” course, we will turn our flash light on each and every part of the puzzle in order to not only to learn about the history of Iran but also to better understand the history of the world. World history is like a relay race and the torch of civilization would have been extinguished by now if it wasn’t for the accompaniment of the people of different lands.

You can read a summary of the content of each session below:

First Session:

-What was happening in the Iranian plateau and who were the people living there?

-What are the ancient civilizations of prehistoric Iran?

-What do the things left of prehistoric times have to tell us?

-What things has Iran’s geography imposed on Iranians’ understanding of the world?

Let’s hear the story of the waters.

Clay human figurine, Tepe Sarab, near Ganj Dareh, Kermanshah (ca. 7000-6100 BCE), Neolithic period

National Museum of Iran.

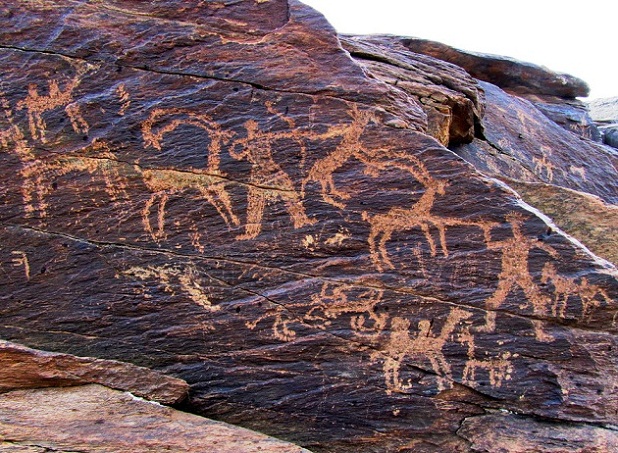

Large numbers of prehistoric rock art, more than 50,000, have been discovered in Iran.

Jiroft vase (2800-2300 BCE), The Jiroft culture also known as the Intercultural style or the Halilrud style, is an early Bronze Age archaeological culture.

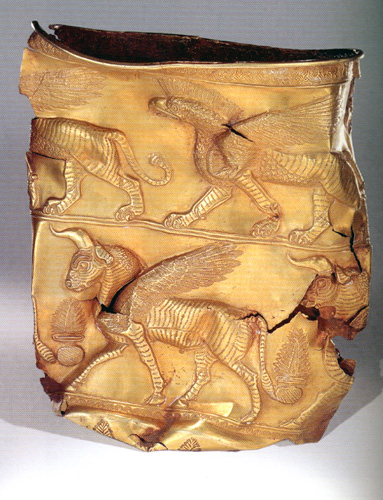

Golden Cup depicting Griffin on top band. Excavated at Marlik, Gilan, Iran. First half of first millennium BC.

Qanat or Kariz is a system for transporting water from an aquifer or water well to the surface, through an underground aqueduct; the system originated approximately 3,000 years ago in what is now Iran.

The Qanats of Ghasabeh, also called Kariz e Kay Khosrow, is one of the world’s oldest and largest networks of qanats (underground aqueducts). Built between 700 and 500 BCE by the Achaemenid Empire in what is now Gonabad, Razavi Khorasan Province, Iran, the complex contains 427 water wells with a total length of 33,113 meters (20.575 mi). The site was first added to UNESCO’s list of tentative World Heritage Sites in 2007, then officially inscribed in 2016, collectively with several other qanats, as “The Persian Qanat”.

Second Session:

-What’s the meaning of Iran’s name and what does it tell us?

-Who are the Aryans and where did they come from?

-Race or language?

-Destructive Aryans or poet Aryans?

-What do we know about the common heritage of Aryans in the ancient world?

-What do Aryan texts or Indo-Iranian texts have to tell us?

Let’s hear the story of Aryans and learn about the traditions left from the ancient days and understand how these prehistoric beliefs are still alive in Iran.

Third Session:

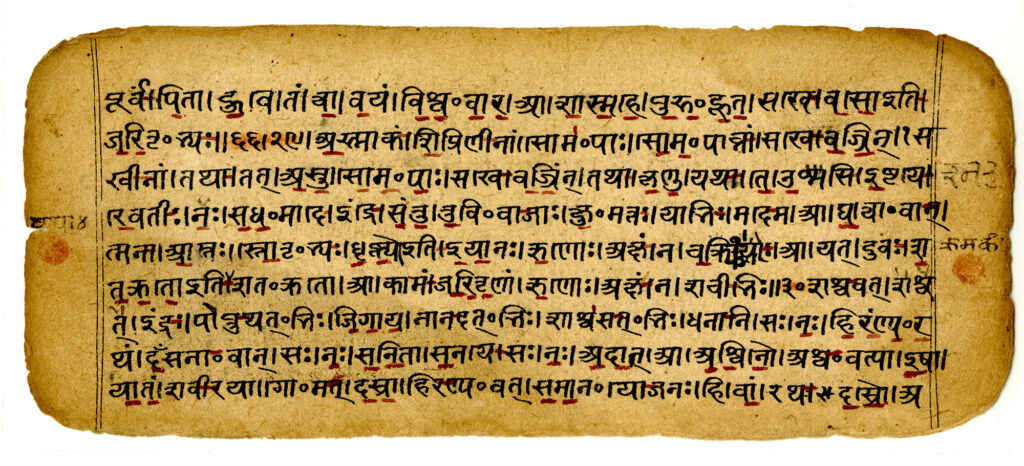

-What do we understand from reading the Vedic texts while considering the India-Iranian heritage similarity?

-How much do we know about Rigveda?

-How much do we know about the other Vedas? And basically why is it important to read these kinds of texts?

-How much do we know about Sanskrit and Avesta linguistic similarities with today’s European languages ?

-What do we know about the common gods of the Aryans?

Let’s hear the story of the Gods who were transformed into anti Gods and continue to see how the traditions related to these Gods are still alive between Iranians and Indians.

Aredvi Sura Anahita, the Avestan name of an Indo-Iranian cosmological figure venerated as the divinity of «the Waters» (Aban) and hence associated with fertility, healing and wisdom.

4th – 6th century silver and gilt Sassanian vessel, assumed to be depicting Anahita. (Cleveland Museum of Art)

Water worshiping temples all over Iran still exist today and are still considered sacred places. These temples are known by different names among Iranian tribes in each region.

The picture above shows one of the water temples in the Alborz mountains.

Forth Session:

-When do Aryan’s Gods were divided into two groups?

-What was the dilemma that made Iranians and Indians to go separate ways?

-Who is Zoroaster?

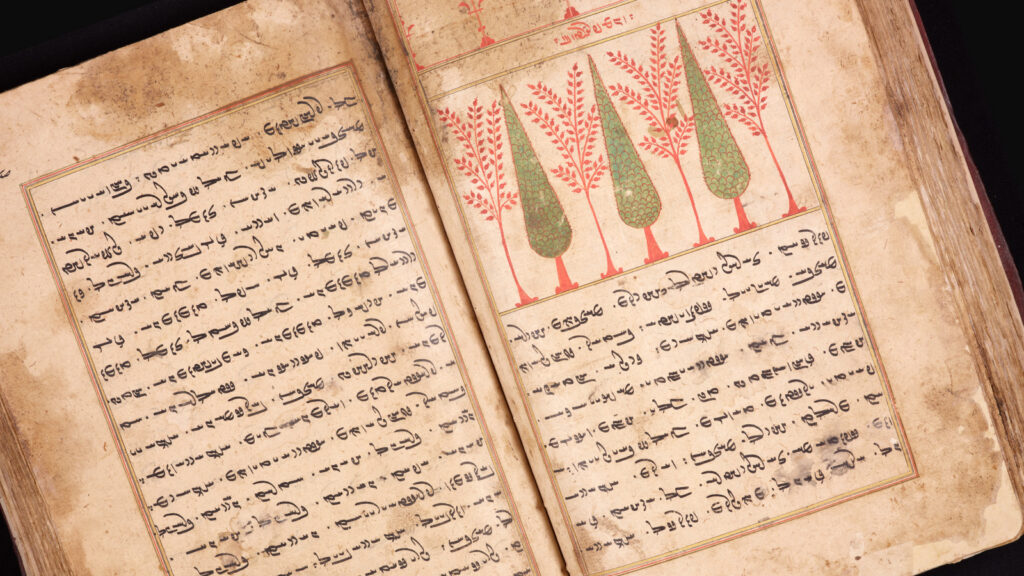

-what kind of a text Avesta is? And what does it have to tell us?

-why is it important for us to read The Avesta?

-What is Avesta’s connection to Zaroaster?

-Is Zoroaster the beginning of an intellectual revolution among Aryans or just another prophet like others in ancient times?

Let’s hear the story of Zaroaster and hear some Avesta hymns and then go to Bahram Fire Temple in Yazd.

Who is Zoroaster?

What is this sign?

Bahram fire that has been kept lit for 1,500 years.

Let’s sing some verses from Avesta together and hear the voice of Avesta singing from two thou-sand and five hundred years ago.

Fifth Session:

-How did Zoroastrian Iranians see the world?

-Is Iran a Zoroastrian land in ancient times?

-What are the other important religions of this land and how did each of them influence Iranians’ understanding of the world?

-What impact did Mithraism, Manichaeism, Gnostic religions and Christianity have in the meantime?

-How familiar are we with the stories of the ancient gods of this land?

Let’s hear the story of the Iranian gods and then go to an assembly on the side of the Persian Gulf, which is the remnant of these rituals.

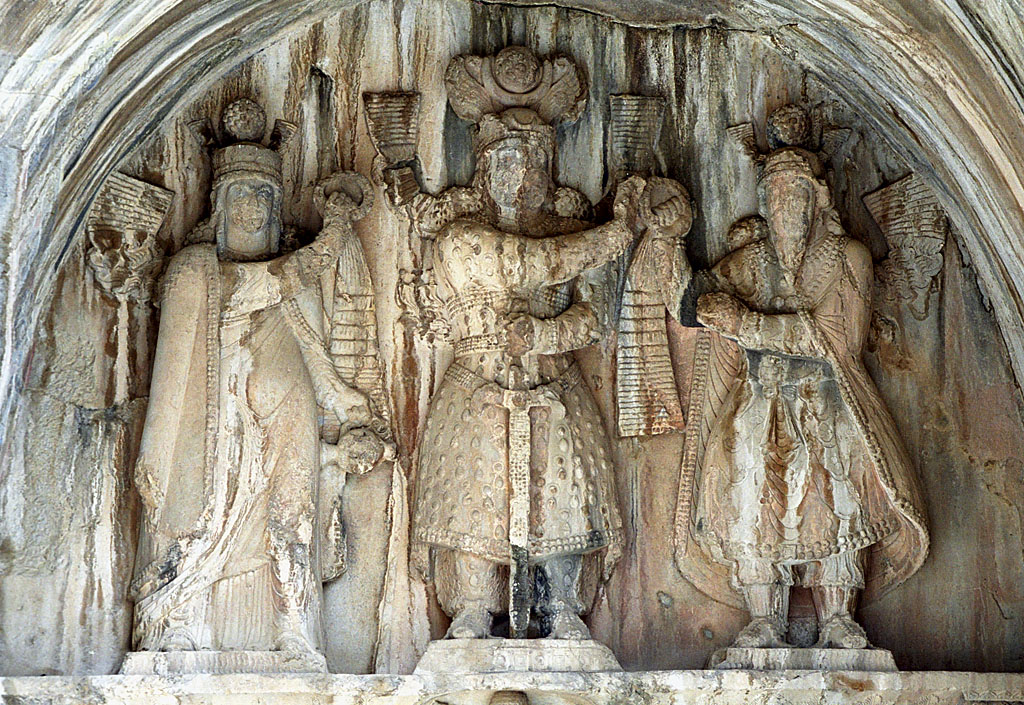

Taq-e Bostan high-relief of the investiture of Khosrow II (590 to 628). The king (center) receives the ring of kingship from Mithra (right). On the left, apparently sanctifying the investiture, stands a female figure generally assumed to be Anahita

God Mithra on the rock relief of Shapour II (309-79 BCE) at Taq-e Bustan

Vayu, ancient Iranian wind-god, likely related to the Hindu god Vaayu. On both sides of the Persian Gulf, there are many rituals in praise of the winds.

Sixth Session:

-What do we know about the history of Iran BC?

-Which powers were of global importance at this time?

-How did Iranian people change the course of world history forever?

-What do the texts of the inscriptions tell us?

-Are these texts historical or literary texts?

Let’s hear the story of the Achaemenids and then visit Pasargad and Persepolis and other Achaemenid buildings and learn about the architecture of this era and finally search for the remaining works of music and dance of that time in contemporary Iran.

How do these reliefs refer to mythology and astrology?

Karnay, one of the ancient Persian musical instruments, 6th century BC, Persepolis Museum.

Members of a Tajik Military Brass Band playing Karnays.

The sword dance on the tunes of the Karnay, Qashqai tribe, Yazd province.

The wood dance of Khorasan, which is actually the preparation of soldiers for war.

Seventh Session:

-How did Middle Persian texts bring the East and the West together, about two thousand years ago?

-What do we understand of Parthian Empire and Sasanian Empire over one look?

-how does the hidden and obvious worldview in Middle Persian texts shapes the today of Iranians?

Let’s hear the story of the Pahlavi language and literature of the Sasanian era and then see its reflection in Iran today.

Plate with a hunting scene from the tale of Bahram Gur and Azadeh. Bahram Gur is pictured shooting the bow, and Azedeh is behind him, handing him arrows.

Eighth Session:

-What do we know about Pahlavi texts?

Let’s read the Asuric Tree together and then learn about the oldest animation in the world.

-How did the world begin and how did we appear in this world?

-How did the earth first have one land and then water covered the world and then that one land was divided into seven lands?

-How are monkeys placed in the order of humans?

Let’s read parts of Bundahishn together and see how mythical geography changes the geography of contemporary Iran in the minds of Iranians.

Animation created with the images on a pottery goblet (c. 3178 BCE) found in Shahr-e Sookhteh.

You can find a conversation between a goat and a palm tree in the story of the Asurig tree, in the Middle Persian texts of the Parthian period, which is reminiscent of these motifs.

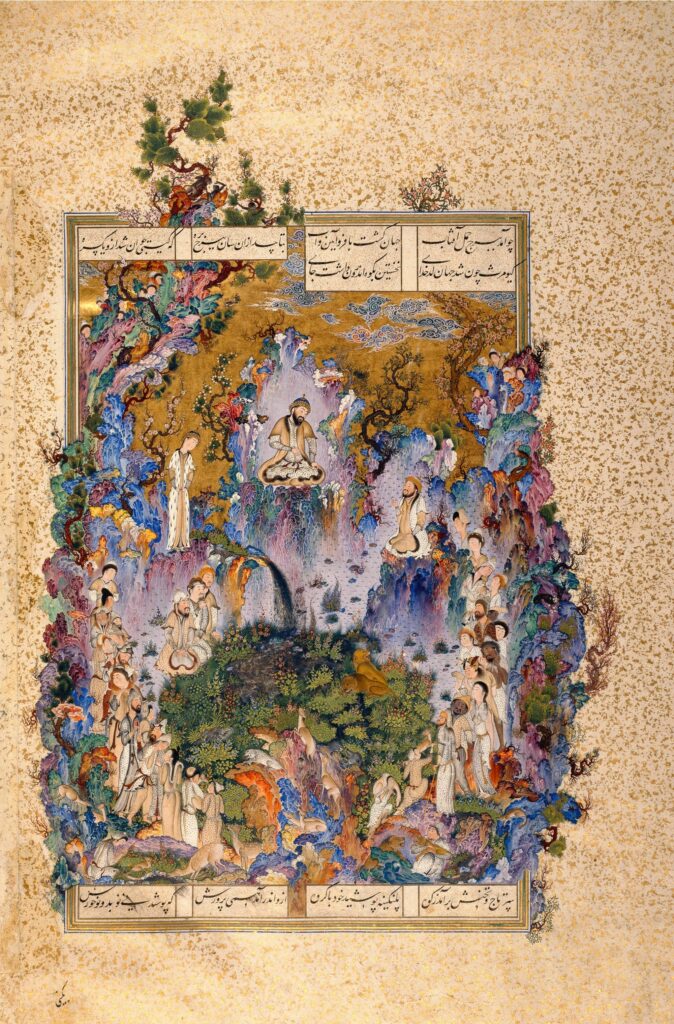

You can find some of the stories that are mentioned in the Shahnameh several centuries ago in Bundahishn.

Ninth Session:

-What do Pahlavi advisory texts have to teach us?

Let’s read some Advisory text together and then observe its reflection over native songs of different regions of Iran and after that go to a ritual in Bushehr.

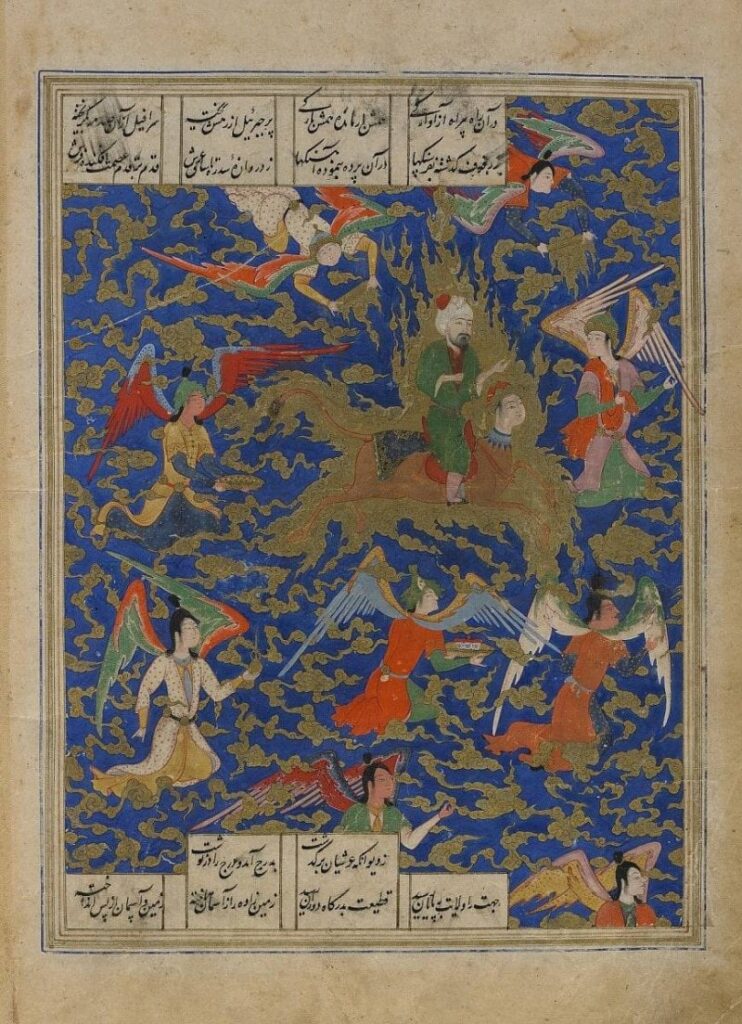

-Where is the origin of Dante’s Divine Comedy?

-Let’s read a summary of the “Book of Arda Viraf” together.

Tenth Session:

-Now that we have reached this point, How is the thing we learnt so far going to be helpful and working for us?

-How has one of these been manifested in Iran’s culture after Islam?

-How does this worldview find its way to our times?

Let’s take a look at Iranian rituals together and sneak a peek at different corners of Iran.