An event by Ali Ettehad

written, directed and music by Ali Ettehad

with 366 Performing Arts Group

Niavaran Cultural Center, Tehran, Iran

April – 2021

Ali Ettehad: I presented “The Endless Maze of Memory” as an event. In the tradition of the performative works of the 1960s, an event is a piece which uses various elements of other medias such as literature, music, drama, performance art, games and etc. to create a single whole; A whole that is made of independent fragments.

“The Endless Maze of Memory” is made of ten independent short theatrical pieces in the form of a monolog or dialogue. The event is five hours long, and during this time, five loops of each will occur and the pieces, which are described below, will be repeated ten times. Audience can choose how to watch the work or how much time spend watching it.

Each of the scenes of this event can be related to a pre-existing form in the structure of Iranian shows. The performer of the third scene performs the legendary-historical character “Farhad” in the style of old Iranian plays “Ta’zieh”.

Ta’zieh as a kind of passion play is a kind of comprehensive indigenous form considered as being the national form of Iranian theater which has a pervasive influence in the Iranian works of drama and play.

He is not acting in the place of “Farhad” in the conventional way of western dramas, but alternately sometimes plays the role of “Farhad” and then comes out of that role and becomes the “writer” who wrote Farhad’s story. In this performance, the author’s memories are mixed with our imagination of Farhad’s memories. Here, as a writer, I do not have an external presence, but I see myself somewhere in the narrative. This presence is not included in the narrations as we normally expect, but it turns the hero into a person with a split personality, just like the tradition of Iranian “Ta’zieh“.

In this way, the performer of the third scene does not know whether he is “Farhad” or “the author”. This mechanism can also be seen in the second scene.

“Humå” and “Geomarta” are separated from their mythical identity every moment and will sit in the role of the author’s subconscious mind, accessing his memories and considering themselves not similar to him but one with him and returning to their mythical identity. One of the signs of this constant transformation of a character can be seen simply by changing the language of the performers from colloquial to archaic.

Another form that plays a central role in the work is “Naqali”.

Naqali, or Iranian storytelling, is the oldest form of retelling legends in Iran, and it has played an important role in society for a long time. Naqal is someone who tells epic stories. The theme of his stories is mostly about the stories of the kings and heroes of Iran.

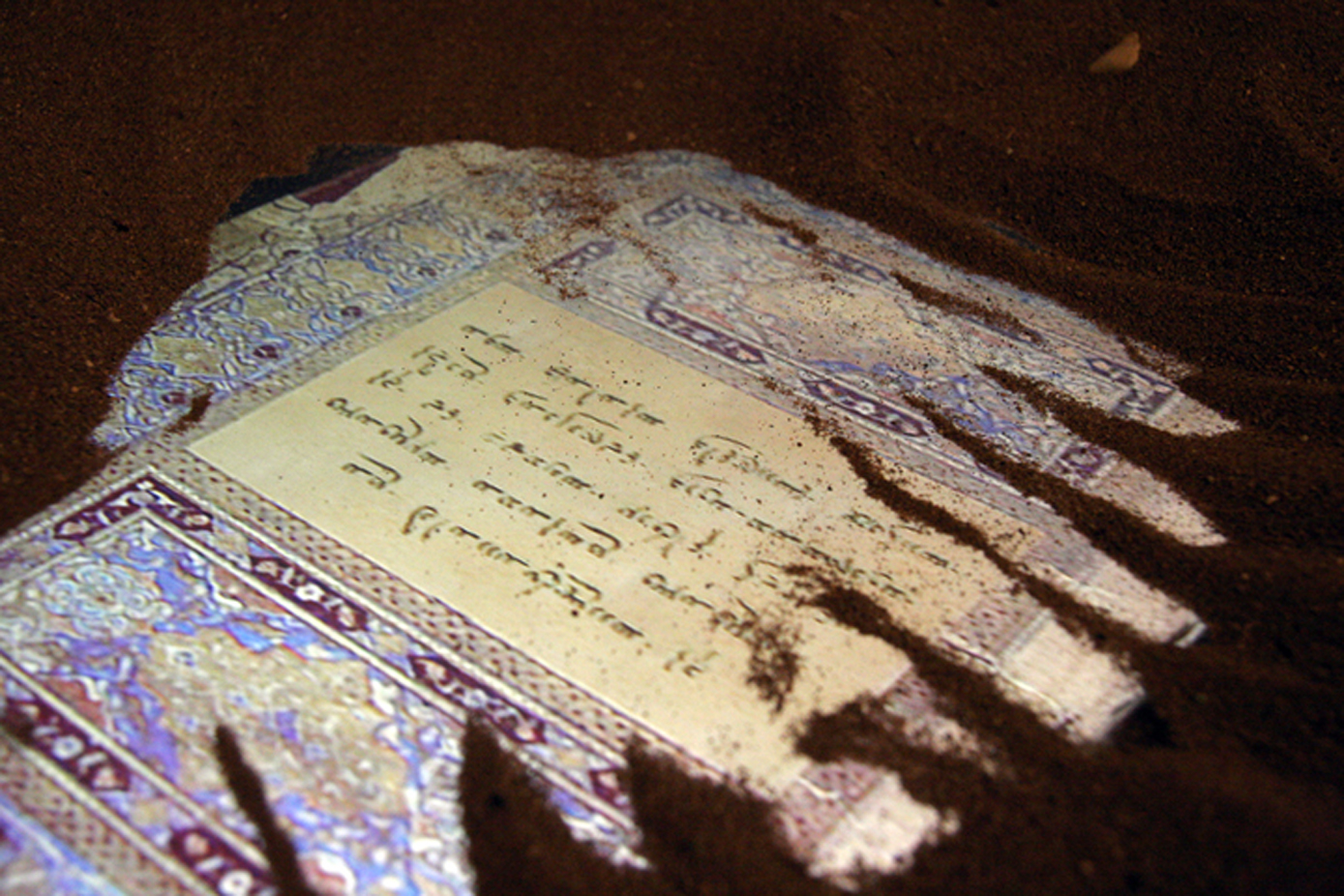

The two performers of this scene perform a fragmented narrative. A schizophrenic structure that, although it is a thousand pieces, but the internal connection of its parts makes it meaningful. This fracture of the image can be compared to Iranian “mirror work”. Thousands of mirror pieces breaking the idea of equality and creating new images. The text of the ninth piece is full of references. References to the “Bible”, to traditions of Iranian folklore, to the history of Iranian painting, to the “Quran” and to the personal life of the author. The fact that in this commentary I constantly refer to the author not as “I” but as “the third person” is because that the character of “I” as the “author” is actually present in the work.

“The Endless Maze of Memory” is an event about the mechanism of storing and analyzing memories. That is, how memories and the human memory system make our individual identity and then the collective identity of a nation. This event is about the layered construction of human identity. It is about the different components of our self-awareness that are formed over time.

We often don’t realize the distant and deep origins of the various aspects of our personality, and yet these are the very aspects of our personality that make our daily decisions. If you are forty years old, you are five years old, three years old, twenty eight years old, thirty five years old and forty years old at the same time. One by one, these are the components that make us and manifest themselves at critical moments.

I must add that the whole work pays attention to history itself, too. And provides an aesthetic reconstruction of the mechanism of human memory. The ten scenes of non-scientific re-creation of what happens inside our human brains; Both in sleep and wakefulness.

How our long-term memories shape our present, and at the same time, the same memories are re-designed based on our present “Psychological economy” in the moment of reviving them and adapting themselves to what makes us present.

as all ten short theaters are being performed at the same time,distant from each other, at different parts of the the garden, sounds and dramatic actions of one another is under another one’s influence and as a result to this compilation and these mutual effects, each of the parts becomes unrepeatable because of these mutual effects.

Pinwheel Garden (the first scene)

Dozens of red paper made pinwheels and dozens of big and small red balls arranged among the greens and trees. Two children (a boy and a girl) are playing in the middle of this arrangement; sometimes with the balls and sometimes with the pinwheels; And sometimes they make something with colored papers. Actually any kind of natural playing a kid would do.

If there is a child in the audience, the child performers of the first scene will allow them to participate; But adults are not allowed to enter this part of the performance and can only watch them from outside.

This is an iconic scene of pure freedom; the kind of freedom that if we have had the chance to experience it once, it is unlikely to be repeated; I say “if”, because many children around the world did not and do not have this freedom. A form of freedom, free from responsibility and duty; Something like floating in the sea where no one drowns.

As I said earlier, adults are not allowed to enter this scene because no one is supposed to pretend anything in this piece.

Children play with red balls and pinwheels as they like while adults try to remember how to deal with those simple tools and this effort reduces their actions to “pretending”!

This scene, while providing a real space for children to play, allegorically reflects the old human brain; that part of the human brain which does not pay attention to the collective consciousness and spends all its power to satisfy the vital drives.

The first scene or Pinwheels Garden is the first floor of the Persian garden of Niavaran and at the same time the outermost. Even if someone does not enter the area of the performance, they can see it as a passerby. For both the adults, who watch from the outside, and the children who participate. Most of the participants of this scene may not realize that they are watching a performance.

The children performers of the first scene do not have a restrictive recipe. Although both of them are young theater actors, they are asked to play freely during the five-hour performance and are even allowed to choose their audience. So, this freedom has also been applied in the performance method of the performers.

Humå and Geomarta (the second scene)

Before I describe this scene, I must give a mythological explanation about the names of the characters here. “Humå” (in ancient Persian) or “Sumå” (in Sanskrit) is a mysterious plant whose nature is unclear today.

In the text of Avesta (the ancient and sacred book of Iranians), Humå is a plant whose extract was used as a psychedelic for sacred rituals. However, in Pre-Zoroastrian mythology, Humå includes wide meanings. Humå in Indo-Iranian scripture Rig Veda is both a god and a priest, and both a sacrificer and a victim; Perhaps it can be said that Humå is the mysterious plant of life of this planet. It is from Humå that fertility gods get power. It is from Humå that people’s prayers reach the gods, etc.

“Giyå Må’retan” or “Geomarta” or in modern Persian “Kiyomarth” is made from two parts “giyå” (meaning living) and “Må’retan” (meaning dying or mortal), which generally means “the mortal living”. In the Avesta, he is considered the first human.

However, when we search other texts, we know that “Geomerte” has a wider meaning. Perhaps he refers to the first “material life” more than he refers to man. In “Bondaheshn” (a philosophical and mythological text related to the Sassanid era of Iran and belonging to the pre-Islamic culture), He is the first human created by Ahura Mazda (the great wisdom of Persia). He lived in the mountains for thirty years and after his death, two plants grow from his body; Two narrow and simple stems in the shape of a rhubarb. Stem that twists and grows. After these two plants grow, they form the species of humans.

In the second scene, on the two sides of a tree on the second floor of the Persian garden, two young women are sitting, one named “Humå” and the other“Geomarta”. Three other performers (three young men) are sitting around the two, and are quietly flipping through old photo albums. The albums contain old photos of the author’s family, belonging to the 1940s till 1970s. Three young men sometimes separate a photo from the album; From time to time they write things in their notebooks; Sometimes changing the place of a photo and sometimes getting up looking for another album.

The conversation between “Humå” and “Geomarta” is about nature and the confrontation with the sublime matter. Their conversation constantly refers to a memory of the encounter of the “Writer” at the age of four with a herd of Caspian deer in the Hyrcanian forests of Mazandaran. A four-year-old child (which goes back to my personal memory) is picking mountain violets with his father in a forest where a herd of Caspian deer passes by in the days before Nowruz (Persian new year eve), And this memory in particular, becomes the axis of the child’s memories when thinking about the encounter with nature. These two performers constantly challenge the audience about their encounters with wild nature through their dialogues.

At the beginning of this scene, “sublime matter” is addressed as “giant” and gradually during the narration, the giants are named and we will know that these giants are actually the life of nature, a nature that today seems far away and is damaged. Modern life, at least in Iran, has separated the human life cycle from the animal world so much that the real life of the earth slowly seems “extra-terrestrial” in the eyes of the modern Iranian citizen.

The memory that is the main focus of this scene is an icon of our linguistic understanding. I say that we are separated from the world around us, and I mean that form of separation which is the result of addressing. We say the word deer and then we learn that differences do not play a role in our address. Deers are big, small, with or without horns, brown and black, spotted or without spots… They are all just deer.

In the final part of the dialogue between the characters of this scene, two performers directly ask the audience if they have had a direct experience of encountering wild nature.

Hume asks the audience: “Have you ever hugged a hedgehog? What about wild rabbits? Did you play with wooly worms whose backs are full of colorful gems?” And so on.

And at the end, the language of the performers changes from Farsi to Mazandarani and the work ends with them singing an ethnic song from the north of Iran. This second short theater of this event is as if being in a longing for a past that cannot be revived. Not only the associations but also the language emphasizes this longing; A language that is one moment modern and one moment archaic. And at the end, you should pay attention to the role of “Humå”. Let’s remember that Humå is a magical plant whose extract puts the drinker in pure unity with the world around her.

Farhad’s Stone and The Pomegranate Tree (The third scene)

Sassanid King, Khosrow, became an Armenian princess, named Shirin, lover. This romance is one of the most famous romantic stories in Iranian literature. However, it is full of frustration and suffering. Every time Shirin makes a new condition for Khosrow to test him. Until when the separation between these two ends, the rumor of khosrow falling in love with another woman spreads in the country. Shirin hearing this news, leaves the palace and settles in a mountain.

In order to win Shirin’s heart, Khosrow decides to build a palace for Shirin in the same mountain. He is looking for an artist and an engineer to build the palace. Until he learns about Farhad’s fame and promises him a lot of wealth. Farhad, who does not want to sell his art, gets angry and rejects the king’s offer. But after a short time, he hears about Shirin’s beauty and intelligence, and on the other hand, he realizes that Khosrow’s love for Shirin is not that deep.

Farhad sends a message to the king and accepts the offer to build a palace. The work of building a new palace begins, and Khosrow returns Shirin to his own palace. Farhad is busy with building a new palace for Shirin day and night in the mountains. Slowly, the news of Farhad’s love for Shirin is revealed. Knowing about this, Khosrow tries to dissuade Farhad from Shirin, but fails. At the end, Khosrow sends an old woman to Farhad and the old woman gives Farhad the false news of Shirin’s death. When Farhad hears the news, he cuts his head with the hatchet he used to carve Shirin’s statue, and dies. In the folklore narratives, the ending continues that, after Farhad’s death; From the blood of his forehead, which had flowed on the ground, and the handle of his hatchet which sprouts, a pomegranate tree grew. The tree grows and blossoms and bears many fruits every year. And if someone opens its fruits, they are full of ashes, the ashes of regret.

At the same time, this scene has a personal reference. Years ago, when I was seven years old, a 40-meter wall separated our yard from the vacant land of the neighbor. It can be assumed that an empty land in my homeland, in the north of Iran (Mazandaran, which is a green and forested land) will not remain empty. It doesn’t take a year for the plants to cover it. On the wall that separated our house from that land; A Japanese kerria tree (or Japanese golden rose) had grown. Little by little, a small bush turned into a huge tree. I was eight years old when it happened.

The heavy weight of the tree collapsed the wall on a summer midnight. From that night, our yard was connected to a wild garden. Now the window of my room was opened to a pomegranate tree that blooms every year and gives its fruits to my eyes every fall.

Between me and the pomegranate tree, there were intertwining bushes and thorns of wild raspberries. Nested and impenetrable plant walls, which blocked the way to pick and eat pomegranates. That pomegranate tree and I lived eye to eye until I was seventeen. Until one day they cut that garden. And they built a six-story building instead. No one knew that me and that pomegranate tree had been living together for ten years with locked eyes. And no one noticed that I wasn’t even there when they uprooted that garden.

In the monologue of the third theater piece, the performer named Farhad performs a text in which these two stories are completely mixed. “Farhad” who talks about the pomegranate tree, one moment refers to the pomegranate tree and one moment “Shirin” (notice that it means “sweet”). One moment it is the pomegranate which is sweet and one moment it is his lover who is sweet. In the way of memories, this memory is perhaps more than anything else an example of “lost desire”. This confusion is also linguistic. Our self-awareness works through language, and for this very reason, whatever is understood through language automatically delays the transmission of meaning.

Passage of the Dreamer (the forth scene)

In this scene, the “dreamer” (a young woman) is sitting behind a vintage typewriter, writing down the dreams of the “author” and reading every sentence she types and slowly completes the dream ’s narrative. “Dreamer” has three companions who slowly take the typed pages from her and walk in the garden and read some pieces of dreamer’snarrative to the audience and after reading that part, they hand the sheet to the audience and return to “Dreamer” again.

So far, every scene of the event is a reconstruction of a part of the mechanism of recording and reviving our memories; More than anything, this scene is an icon of one third of our life that passes in unconsciousness. We spend a third of our lives sleeping and this part of our history is often neglected. However, our brain experiences a special opportunity to establish neural connections during sleep, especially during REM. It is precisely because of the different activity of the brain in this unconscious experience that many mental puzzles are solved during REM sleep. Or many trials and errors that we don’t have the courage to do while awake are done in this stage of sleep.

The dreams that the “dreamer” narrates and writes take place in an intermediate land; somewhere between this world and another world; Just like the mythical creatures that are mediators between earth and sky. Those figures hidden under the veil also show that they are the inhabitants of the world, visible and invisible at the same time.

For me, writing was the first tool to cross the world of childhood. I have been writing since I can remember. My first memories of writing are related to the time when I knew how to read and not how to write. I was five years old. I remember well that I used to draw things on five or six centimeter lengthen pieces of paper (similar to Persian script and sometimes Roman script) and then I would form them in the form of a book, and then of course I would clearly know what to read from those meaningless lines.

I had not finished elementary school yet when I wrote something; This time something long.

I thought it was a long novel (written in a hundred-page notebook) in the tradition of Isaac Asimov’s novels, and I gave it to my mother as a birthday present. My mother still has it. But I haven’t had the courage to read it or even see it all these years. I was twelve years old when writing became more serious to me. I used to write things for myself and then little by little from the same year I learned to write in the adult tradition. Then I sent the things I wrote to the magazines of that time. Of course, I didn’t say anything about my age and they didn’t ask anything about it either. A little later, some of my writings were published. When I was thirteen years old, the magazine of political satire, which was very famous for years – Gol Agha – sent me a list of topics every month, and it goes without saying that I also felt that I had become a writer.

I didn’t have a typewriter in those years; But I wished I had one. For me, this typewriter is the code of discovering writing, and those assistants who accompany the “dreamer” are her long arms that spread the texts everywhere in this small world (the garden of the performance).

In Search of The dragon Slayer (the fifth scene)

In the mythology of Iran and the neighboring lands of Iran, an eternal struggle is described between the gods of rain and dragons or demons of drought, which finally ends with the victory of the gods of rain. In the fifth scene, the “Dragon” character, while holding a small camera connected to several televisions with a cable, searches for the Dragon Slayer and the Drought Remover God among the audience and does not find it. The performer constantly takes his camera on himself and his audience, and the pictures are broadcast on the televisions behind him.

The dragon does not accept to win the field without a fight. He is looking for a brave opponent. He constantly counted the characteristics of “dragon slayer” based on Indo-Iranian mythology. He calls “Bahram” and “Indra” and searches for them among his audience. He knows that his duty is drought and with all this drying up the world without any difficulty does not bring him any pleasure. He reminds his audience that they have dried up the lakes of Iran one by one.

Small bags full of salt are hung from the dragon’s clothes, and every time a part of the dragon’s monologue ends, he opens one of the bags and randomly empties it into the palm of an audience member. He reminds them every time that a lake dries up it is the salt that remains from him.

In the way that this event explains the mechanism of recording and analyzing and reviving memory in the human mind; This scene refers to aspects of our understanding whose roots go back to previous millennia. A large part of our daily life is under the powerful influence of the collective consciousness. Collective psychological coordinates are created with this, which are passed from one generation to another without the need for direct education. This is how, in a certain situation, a sense of shame or a sense of victory suddenly takes over our society.

This monologue has other aspects; One is that the video camera used in the work has a quality that is distinctly reminiscent of home video cameras of the late 1980s and early 1990s. The memory of the generation that I grew up in is tied to this quality video. The camera with which the performer takes pictures does not have a recorder, and as a result, what he sees is translated into a video image at the same moment, but is immediately forgotten. This kind of ephemerality and oblivion has a direct relationship with the type of narration of this scene.

Television images are small or large based on the distance and proximity to the camera. This smallness and largeness of the images in the narrative that “Dragon” is making has a direct reference to the tradition of Pardeh-Khani* (tableau reading) for me.

In the Pardeh-Khani’s paintings, the main characters are bigger and the secondary characters are smaller; Just like medieval miniatures, the narrator would complete his narrative by pointing to the heads and bodies within his pointer. Here, the story-tellers pointer is replaced by a small camera.

*) Pardeh-Khani is an Iranian tradition in which a minstrel or a storyteller narrates a legend, a mythical narrative or a religious story using a large painting that is full of different narrations and characters.

Golchehr and Orang (the sixth scene)

From dozens of Persian love stories, among all the most famous names, “Golcher” and “Orang” are the only couple who have been mentioned many times in famous works of Persian literature, but their story is nowhere to be found. Their presence in Persian classical literature has been reduced to fleeting mentions, and the original narrative of them has been lost in the maze of history. They have been mentioned, but no story of them has been left.

In the sixth short theater, a young man and woman create an imaginary narrative of “Golcher” and “Orang”. This narrative is constantly shifting in the layers of history. Sometimes it goes to the 1940s and sometimes it comes to the present age and sometimes it floats in the ancient Indo-Iranian texts. This timeless romance can represent pieces of our romance and that of our fathers and mothers. For me, these memories are a representation of our mental wishes; Desires that are not survival but abstract and with their help, human civilization has taken shape.

Some of these memories go back to the occupation of Iran by the Soviet Army during World War II. The Red Army occupied the northern parts of Iran in the 1940s. My father was born right around this time. A part of the conversation between “Orang” and “Golcher” goes back to these years. To the occupation of my hometown in the north of Iran by the Soviet army or to the snow tunnels through which my father’s childhood reached his school.

Each of these pieces is an excuse to build a historical puzzle; A puzzle that creates a timeless romance. Among the romantic dialogues of this scene, sometimes mythical manifestations of a non-tangible and heavenly lover can be seen. In the mystical culture of Iran, there is no boundary between “divine manifestation”, “beloved” and “mythological gods”. Rumi talks about the creator and soul of the world as if he was talking about his lover. He hugs them, kisses them and sleeps with them in the same place and wakes up with them; As if they are not the creator and soul of the world, but a woman or a man.

The dialogue between “Orang and Golchehr” has such continuity. When there is no boundary between “Divine Manifestation” and “Beloved”; How can it be expected that there is a boundary between the lover and the beloved, or between the author and the subject of writing. Or how else can we say that there is a boundary between “love” as an abstract meaning and the “beloved”.

In Rumi’s poetry, the narrator is one moment beloved, one moment a lover, one moment a mystic, one moment the idea of love itself, and one moment it is God who speaks. The scene of “Golcher and Orang” also has this feature and the characters are floating.

Earlier I said about Ta’ziyeh, and now I have to remind you again that the sixth scene of the play also uses the fluidity characteristic of Ta’ziyeh.

The Game of Eyes (the seventh scene)

In the seventh theater piece, the performer is sitting in front of a game board and invites the audience to play with him. In this game, only the audience has pieces and their moves are determined by dice. In each marked house, a card is drawn and read by the performer. The card asks them to talk about their memories, their fears, their dreams, their childhood, the recipe of their favorite food, etc. The winner of the game can come to the event one more time without buying a ticket.

This scene symbolically represents our attempt in adulthood for a playful experience; It is supposed to put us in a situation similar to our childish freedom for a few minutes.

The performer of the seventh scene plays a split character. He is an adult man who behaves like a child, and an invisible figure standing to his right constantly orders him to stop acting like a child. He leads the game with his audience. Without having a piece in the game, he tries to compete with the audience. He enjoys his opponent’s loss and at the same time pretends to be sad about their defeat.

He wears a cloak and looks mysterious next to his game board, but his behavior is still childish. The performer of “The Game of Eyes” has a contradictory personality, And it is precisely this contrast that creates the central idea of the seventh scene.

The Boat Makers (The eighth scene)

Two performers are standing next to a Persian pool. The ground around the pool is covered with pages of poems and pages of a novel. Two performers ask the audience to make boats using sheets on the ground and then launch the boats into the water. These pages contain fragments of published works. “Boat Makers” are stuck together and have similar behaviors. They walk together and run together and talk together hand in hand. Even when they want to invite an audience to build a boat, they talk at the same time. They do not combine their personal space with the outside space. They whisper in each others ear. They say things to each other by pointing and finally they say something louder so that their audience can hear it.

When one of them is teaching the audience how to make a paper boat, the other reads the text written on the paper which she is holding to the audience or maybe to herself. When she finishes reading that text, she will build a boat with that paper and throws it into the water.

For me, this kind of ephemerality is the summary of human history. I have already discussed this issue clearly in “A Requiem for libricide”. Above all, this scene reflects the possibility of destruction and the mechanism of oblivion in our minds. Forgetting, while it seems cruel, it is liberating. Forgetfulness saves us from suffering.

The Garden of Gadhumå and Apa (The ninth scene)

“Gadhumå” is a female performer (her name means wheat in Sanskrit) and “Apa” is a male performer (his name means water in Sanskrit ). They perform parts of the long text “The Gospel of un-appointed Prophet” against each other; The text that I published six years before this piece. This text is a long narrative about love, faith, failure, victory, memory and most importantly duty.

During her performance, Gadhumå mixes wheat flour and eggs and Appa, on the other hand, brings her bowls of water so that Gadhumå can make dough. In all the moments of this short theater piece, the two performers are engaged in the repetitive action of preparing the dough. The text of this dialogue refers to the history of faith in the world and places it all in the heart of a mythical romance.

This scene is on the last floor among the garden floors; The seventh floor. In my opinion, it is the last stage of human development up to now. For me, who is nearing my forties, the idea of this scene is a summary of all four decades of my life. One by one, these ideas have been manifested in preparing the bread dough. I loved that if this dough was baked in another corner of the garden during the performance and finally The Singer, who is from the tenth scene, gave it to the audience as they left the garden. In every performance, I imagine the smell of bread wafting through the garden, and I imagine the hot pieces of bread in the hands of the audience. It is not an exaggeration if I say that the smell of bread can be a symbol of all human civilization. If you smell bread somewhere, there is no doubt that you have reached a city, a village or a habitable place.

This scene, along with the rest of the scenes, is more than anything else a symbol of the final task that humanity has built its culture on, faith and duty.

The Singers (The tenth scene)

In the tradition of ancient Iranian theaters, the director himself is a part of the play. He is present on stage and guides the audience and coordinates the poems with his actors and sometimes sings and performs with them.

In this event, I am in charge of this role as a director and performer along with a female vocal artist, and during the entire performance, by playing the Persian string musical instruments and performing verses related to the situations, We link various work scenes together.

“The Singers” do not have a specific place or a stage to play on and to be visited on. They walk freely throughout the garden and sit wherever necessary. During the entire performance, “The Singers” can talk with the performers or perform a part of their text or speak or repeat a text before it comes out of the mouths of the performers.

In the psychological mechanism of this event, the tenth scene sits in the position of our individual self-consciousness, which gives a new interpretation of our personal and social memories and lived experience every moment.

Final Scene

Once every hour, all the performers of this event gather around the large pool in the middle of the garden and leave their repetitive actions. It is like a sleep state in which the brain regions are at the same frequency for a few minutes.

Kamran Diba, a renowned architect of his time designed Niavaran Cultural Center. The construction of the complex started in 1976 and finished in 1977.

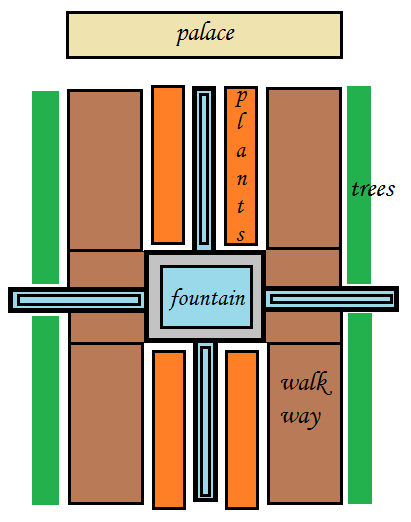

Influenced by the pattern of Persian Gardens, the garden of Niavaran Cultural Center provides great outdoor spaces for artists to hold their performances.

Persian gardens

From the time of the Achaemenid Empire, the idea of an earthly paradise spread through Persian literature and example to other cultures, both the Hellenistic gardens of the Seleucid Empire and the Ptolemies in Alexandria. The Avestan word pairidaēza-, Old Persian *paridaida-, Median *paridaiza- (walled-around, i.e., a walled garden), was borrowed into Akkadian, and then into Greek Ancient Greek: παράδεισος, romanized: parádeisos, then rendered into the Latin paradīsus, and from there entered into European languages, e.g., French paradis, German Paradies, and English paradise. As the word expresses, such gardens would have been enclosed. The garden’s purpose was, and is, to provide a place for protected relaxation in a variety of manners: spiritual, and leisurely (such as meetings with friends), essentially a paradise on earth. The Common Iranian word for “enclosed space” was *pari-daiza- (Avestan pairi-daēza-), a term that was adopted by Christian mythology to describe the garden of Eden or Paradise on earth. The garden’s construction may be formal (with an emphasis on structure) or casual (with an emphasis on nature), following several simple design rules. This allows maximisation, in terms of function and emotion, of what may be done in the garden.

Kamran Diba (born 5 March 1937) is an Iranian architect and museum director, and prior to the Iranian Revolution, Diba worked entirely in the public sector in Iran. He is currently residing in Paris, France.